Improving agile delivery efficiency through DevOps and the technologies that enable its adoption (i.e. microservices, containers and their orchestration) has allowed organizations to leverage new software capabilities. To support this, security functions have evolved to avoid relying on slow manual activities that can hinder or even block delivery, and have shifted to automated security testing methodologies such as SAST (Static Application Security Testing), DAST (Dynamic Application Security Testing), and SCA (Software Composition Analysis) instead. For small companies, having only one dedicated team might be enough to ensure the security of all services and the tools needed to build them. However, as companies grow, it becomes increasingly more challenging to apply the same strategy solely through the introduction of more sophisticated tooling.

Who should be responsible for product security?

The security of a product is proportional to the quantity of time and the quality of effort invested to secure it. In a product-focused organization, the security department serves the business by working with the product and engineering teams to develop the tooling and processes that are necessary to avoid any vulnerabilities.

To achieve this, a positive relationship must exist between security and engineering teams. However, this can sometimes be a challenge since the security teams are often introduced much later in a product's journey. As a result, it’s common that organizations looking to improve their product delivery process will choose a “Shift Left” strategy by introducing security in the Software Development Lifecycle (SDLC). As customers of the service, it's crucial that developers are part of the identification, testing, and configuration of the tooling. Not doing so can create the risk of negatively impacting developer productivity through the introduction of inappropriate or misconfigured tooling. For example, an automated tool can identify a vulnerability without providing clear guidance on how to remediate the issue.

At 10x, we have found that tooling and security gates can take us only so far. As we continue to grow as an organization, we identified several requirements that had to be met in order to maintain our security standards at scale:

- Improvements to developer feedback loops

- Building a model that allows incremental investments in security training

- An efficient mechanism to communicate security changes to the organization

- The ability to catch security design flaws early by supporting features from the bottom-up

Maintaining and improving security at scale

It can help to look at how some non-security functions have attempted to solve the problem. Let’s take infrastructure in a small organization as an example. In this scenario there are usually a small number of feature teams whose focus is mainly on building microservices, and so they lack the demand for a dedicated infrastructure engineer. Therefore, a core infrastructure team can be ideal as it can easily support the feature teams to build, deploy, run and monitor their services.

However, attempting to scale with this model can result in bottlenecks, dependencies, unclear ownership and a "throw it over the wall" mentality, which can have a knock-on effect on growing and retaining talent due to poor knowledge sharing and toil. It also requires the infrastructure team to scale in proportion to the number of teams, which can make this approach quite expensive. One way of solving this problem is by embedding an element of responsibility within the engineering teams. This is not a new idea, since it is not unusual for QA (Quality Assurance) teams to have dedicated engineers as core members of each team, despite the presence of a centralized function.

For security, it should be no different because getting this wrong can potentially have greater adverse effects on culture and morale due to their position in the delivery lifecycle, and often being seen as the team that always says “no”.

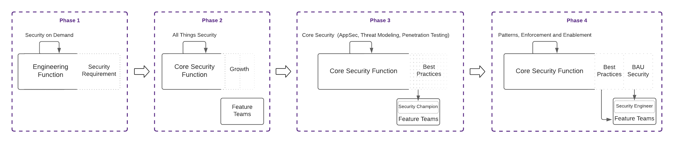

At a high level, an organization should first identify the business requirement (phase 1) and proceed to fulfill it by bringing on individuals to meet the demand (phase 2). Once the requirements to scale begin to appear, the initial conditions change, and the central model is rarely suited to meet the needs. This results in decentralization with a shift into the engineering teams (phase 3), followed possibly by the need to introduce full-time core members for critical teams (phase 4).

Implementing a decentralized approach

At a practical level, a ‘Security Champions’ program can be the first step in introducing security as a core part of an organization's culture. The goal here is to bring security and engineering closer, to encourage them to collaborate and not to shift the responsibility altogether. However, changing an organization's culture and mindset is a slow process, and one where mistakes can be costly. To limit the impact of such mistakes, developers must be given the time and resources to adopt the mindset first. Therefore, it’s imperative that an organization's leadership agree on the proposition’s value.

Here at 10x, we've designed our program as such:

- It is the responsibility of the teams to nominate their security champion

- Every engineering team must have a nominated champion, but smaller teams can be grouped together

- A champion does not have to be an engineer as it’s important to holistically represent the SDLC

- Security champions should also be nominated for non-engineering functions. They’re a major part of an organization’s security posture and must not be ignored

- Once nominated, all champions are given the resources and help they need to support their teams. At 10x, we hosted a bootcamp on fundamental security concepts. Specifically, threat modeling, application security and detection engineering

- Members of the program are given one day, every two weeks to focus on security. This doesn't have to be focused on resolving vulnerabilities or threat modeling. It can be used to engage with the wider security community and stay updated with changes to the threat landscape

- Host security events on a periodic basis to present new proposals, security research and technologies

Engagement in the program is key and so it's important that members have a mechanism to interact with each other and to ask difficult and awkward questions. The medium of interaction is not particularly relevant, but we have found that a quick async messaging space works best. The responsibility of setting the tone and creating the space for these conversations lies with the core security teams.

How to build for success

The Security Champions program can allow an organization to scale security both horizontally and vertically by setting the baseline of skills required within a development team. Strategically, as the requirements increase, all team members will be able to perform the function of today's security champions and where necessary, one or more full-time security members can be introduced within a team.

For the program to succeed, there are several guiding principles we adhere to at 10x:

- Security champions feel empowered to act as the voice for security within their teams

- They don't need to have all the answers but should be able to nudge their teams in the right direction

- Security champions are an extension of the security team and therefore can easily leverage the experience of core security members

- Where core security teams intend to change a fundamental element of a product, security champions are the entry point to development teams

Ultimately, engineers should not see security as the team on the other side of the wall who critique their work and slow down delivery. Instead, it should be clear that engineers own their code and are responsible for developing it securely but are not alone in this process and have a familiar mechanism to seek support. Additionally, it creates a cohort of individuals who can raise concerns and help identify systemic issues faced by their teams before the problem becomes chronic.

Conclusion

Establishing a Security Champions program at 10x has allowed us to adopt a mechanism of continuous development for our engineers through security presentations by both internal and external presenters. It helps our security teams navigate the organization and creates a space for core members to develop materials that reach engineers outside of the program and communicate information efficiently.

Security is not software engineering but building a security function is not drastically different from building other non-software engineering functions. The proposed model will undoubtedly evolve with the industry and be tailored to your organization. It's critical to identify your requirements, check whether you are meeting them today and consider if you are at the right stage of maturity to implement this approach. As with any plan or design, it must be re-evaluated on a periodic basis to enable continuous improvement and future development.